Harlem Late Night jazz Presents:

Hip-hop/Rap: 1980

HARLEM LATE NIGHT JAZZ Presents:

Hip-hop/Rap: 1980

The Jazz History Tree

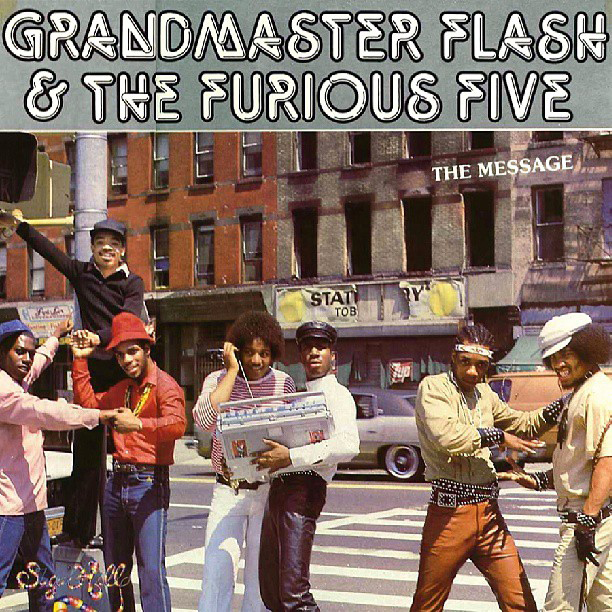

Said to be coined by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five member Keith “Cowboy” Wiggins, the music movement of hip-hop can be traced back to a “burnt out” South Bronx in New York City in the 1970s. It was created in the poorest, most neglected ghetto of New York City by black and Latino teenagers, as part of a hip-hop culture that also produced rap, breakdancing, and graffiti art. The term hip-hop music is sometimes used synonymously with the term rap music, although rapping is not a required component of hip-hop music.1

The most rejected youth of America used rap to speak the truth of their lives “in your face” (out for all see). However, hip-hop music did not get officially recorded for radio or television until 1979, largely due to a lack of acceptance outside ghetto neighborhoods. At block parties, DJs played percussive breaks of popular songs using two turntables and a DJ mixer.2 Rapping developed as a vocal style in which the artist speaks or chants along rhythmically with an instrumental or synthesized beat. Hip-hop is deeply rooted in the African traditions of call and response and ring shout.

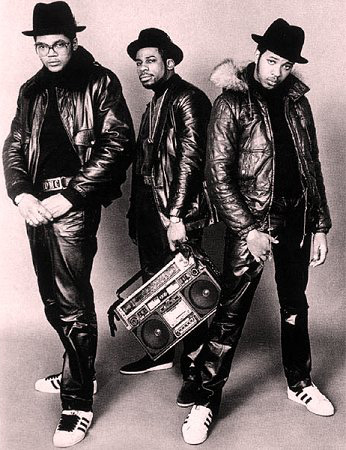

Like prior Jazz genres, Hip-hop’s emergence was initially impeded by the music industry’s resistance to marketing this new Black underground music. MTV and pop outlets refused to play Hip-hop. However, Rap artists quickly resorted to producing their own music and employing innovative street level marketing efforts with great success. Black Entertainment Television, led by Robert Johnson, later grasp this opportunity, aired Hip Hop videos and grew to a multibillion dollar enterprise. This marketing revolution, led by Hip Hop, opened the door to musicians of all Jazz genres to have more control of their music and often more income.

It’s important to note that Hip-hop’s mercurial success led to Hip-Hop “only” radio stations targeting youth of all ethnic groups. This development, I believe, created the second great schism in Jazz, disconnecting Black youth from the music of prior generations. Bebop’s lack of “danceability” created the first. These schisms are still being “healed” today as young musicians are now reaching back and embracing all the branches of the Jazz Tree.

The Sugarhill Gang’s 1979 song “Rapper’s Delight” is widely regarded to be the first hip-hop record to gain widespread mainstream popularity. Notable artists at this time include DJ Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, Fab Five Freddy, Marley Marl, Afrika Bambaataa, Kool Moe Dee, Kurtis Blow, Doug E. Fresh, Whodini, Warp 9, the Fat Boys, and Spoonie Gee.3

Hip Hop’s “Golden age” or “golden era” is the description given to mainstream hip-hop produced between the mid-1980s and the early ’90s, which is characterized by its diversity, quality, innovation, and influence.4 5 There were strong themes of Afrocentrism and political militancy in golden age hip-hop lyrics. The music was experimental, and the sampling drew on eclectic sources.6 There was often a strong jazz influence in the music. The artists and teams most often associated with this phase are Public Enemy, Boogie Down Productions, Eric B. & Rakim, De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, Gang Starr, Big Daddy Kane, P-Diddy, Will Smith, Nas, and the Jungle Brothers.7

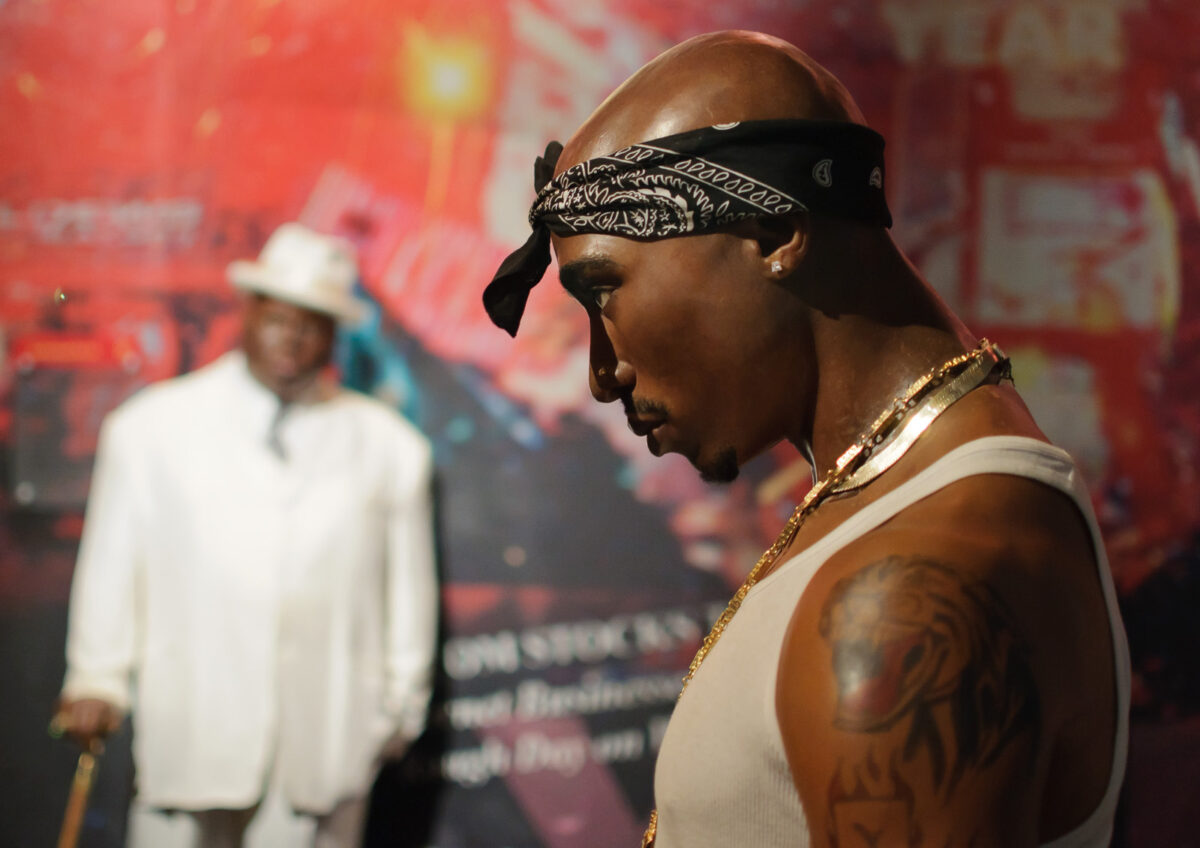

Gangsta (gangster) rap, a subgenre that often focuses on the violence and poverty experienced by inner-city black youth, emerged during this wave. Schoolly D, N.W.A, Ice-T, Ice Cube, and the Geto Boys are key founding artists. On the West Coast, G-funk dominated during the 1990s, with artists such as Tupac, Dr. Dre, and Snoop Dogg. East Coast gangsta rap icons included Kool G Rap and the Notorious B.I.G., while East Coast hip-hop was dominated by the hardcore rap of artists such as Mobb Deep, Wu-Tang Clan, Onyx, and the Afrocentric jazz rap and hip-hop of Native Tongues.

In the mid 90s hip hop icons Jay Z, and Sean Puffy Combs (P Diddy) emerged in New York. These trailblazers (initially, out of necessity) took control of and produced their own music; went around the established music companies; marketed their own labels and brands in innovative ways. The Hip Hop generation, perhaps more than any that proceeded it, “freed” Black musicians from the control of music companies and paved the way for many to reap the financial benefits of their art. In 2020 Jay Z’s net worth was estimated at $1billion, Kanye West at $1billion, P Diddy at $855 million, and west coast rapper, Dr Dre, at $820 million.

The popularity of hip-hop music continued through the 2000s. Dr. Dre remained an important figure, producing the Marshall Mathers LP by Eminem, a white rapper from Detroit, in the year 2000. Dre also produced 50 Cent’s 2003 album Get Rich or Die Tryin,’ which debuted at number one on the US Billboard 200 Chart.8 Eminem was to become the largest selling rapper of the 2000s. His estimated net worth was estimated at $210 million in 2020.

Women hip hop/rap artists are sometimes overlooked, but—just as they were with the blues— women were pioneers of the movement from the beginning. The first female solo rapper to release her own, full-length album was MC Lyte, with “Lyte As A Rock” in 1988. Notable female hip-hop artists include Queen Latifah, Missy Elliot, Monie Love, Salt-N-Pepa, Lil’ Kim, Bahamadia, Foxy Brown, Lauryn Hill, Remy Ma, Eve, and the “Queen of Neo Soul,” Erykah Badu.

Footnotes:

1 Jake Coyle, “Spin magazine picks Radiohead CD as best,” USA Today, June 19, 2005.

2 Michael Eric Dyson, Know What I Mean?: Reflections on Hip-Hop, Basic Civitas Books, 2007, p. 6.

3 Peter Eisenstadt, ed. “Hip hop,” The Encyclopedia of New York State, Syracuse University Press, 2005.

4 Jon Caramanica, “Hip-Hop’s Raiders of the Lost Archives.” New York Times, June 26, 2005, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/06/26/arts/music/hiphops-raiders-of-the-lost-archives.html.

5 Jake Coyle, “Spin magazine…best,” USA Today, June 19, 2005.

6 Roni Sariq, “Crazy Wisdom Masters,” April 16, 1997, Archived November 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, City Pages.

7 Cheo H. Coker, “Slick Rick: Behind Bars,” Rolling Stone, March 9, 1995, archived February 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, https://archive.org/web/.

8 Billboard, “Charts History: 50Cent,” https://www.billboard.com/music/50-cent/chart-history/ .